DLP Bioprinting: High-resolution biofabrication designed for cell viability

Learn how DLP Bioprinting is shaping the future of physiologically relevant tissue models and multi-material co-cultures, and how CELLINK’s 3D bioprinters are driving breakthroughs in regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug screening research.

Bioprinting precisely positions living cells, biomaterials, and bioactive molecules to fabricate tissues, organ-like structures, and physiologically relevant models, revolutionizing personalized medicine, tissue engineering, and drug discovery. Digital light processing (DLP) bioprinting is a light-based 3D bioprinting technology that combines biocompatibility with high feature resolution. DLP Bioprinting minimizes mechanical stress on cells while achieving micro-scale resolution, ideal for advanced biomedical applications, including new approach methodologies (NAMs), microphysiological systems (MPS), and complex tissue engineering.

What is DLP Bioprinting?

DLP Bioprinting is a light-based 3D tissue fabrication technique adapted from stereolithography (SLA). It uses digital light projection to solidify entire layers of a photocurable bioink in one step through a process called light-induced polymerization¹ or photopolymerization. Unlike extrusion-based methods that mechanically deposit inks, DLP Bioprinting technology uses patterned light to cure material with micrometer precision producing intricate biological architectures at high speed².

This process begins with a light source of a specific wavelength (e.g. 405 nm) emitting light onto a digital micromirror device (DMD) that generates a 2D pattern of visible light onto a thin layer of bioink containing photoinitiators. Only the illuminated regions undergo rapid crosslinking, forming a solidified layer that matches the digital design. The support then moves incrementally, and the process repeats layer by layer, building complex 3D structures with remarkable accuracy, throughput, and reproducibility².

Available DLP bioprinters

CELLINK’s BIONOVA X™ and LUMEN X™ 3D bioprinters harness visible-light DLP technology, reducing the risk for UV-related cell damage while maintaining exceptional pixel resolution, down to 10 µm and 35 µm respectively.

This gentle approach ensures high cell viability, excellent print fidelity, and precise microarchitecture in each print.

Comparison of bioprinting technologies

| Method | Mechanism | Speed | Resolution | Cellular Compatibility | Technology Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Light Processing (DLP) | Full-layer curing via 2D light pattern using DMD | Very fast | Very high (10 μm) | Excellent | Advanced optics and automated calibration ensure microscale precision |

| Extrusion | Bioink pushed through a nozzle | Moderate | Medium (100–400 μm) | Excellent | Versatile, resolution depends on nozzle size and flow stability |

| Stereolithography (SLA) | Laser scans points sequentially | Slow to moderate | Very high (~10 μm) | Moderate | High resolution but slower than DLP; viability varies |

| Masked Stereolithography (MSLA) | Full-layer curing via LCD mask | Fast | High (25–50 μm) | Good | Cost-effective; limited light power, limited pixel sharpness |

| Volumetric | Photopolymerizes entire structure simultaneously | Very fast | High (14–100 μm) | Excellent | Extremely fast; tuned per geometry |

| Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) | Localized polymerization via femtosecond laser | Slow | Ultra-high (<1 μm) | Good | Exceptional precision; expensive & complex |

Biological compatibility: Why it matters

Biological compatibility is the ability of biomaterials and bioprinting processes to support cellular function, viability, and physiological interactions with minimal adverse effects, particularly within tissue-engineered constructs³. With DLP Bioprinting, biological compatibility ensures that bioinks and fabrication methods foster a suitable environment for cells enabling subsequent tissue development and functional maturation.

Cell Viability

Ensuring cell survival after printing is essential for successful tissue engineering, affecting the regenerative potential and biological activity of printed tissues. DLP Bioprinting has demonstrated excellent cell viability, with bioink formulations optimized to protect cells from phototoxicity and environmental stress⁴.

Tissue Integrity

High-resolution DLP Bioprinting enables the construction of tissue models with well-defined microarchitectures, supporting cell spreading, differentiation, and organized tissue formation².

Biomaterial Functionality

Biocompatible synthetic or natural polymers used with DLP Bioprinting technologies enable the creation of scaffolds with tailored mechanical properties, porosity, and degradation profiles, vital for supporting cell growth and functional tissue maturation⁵.

Low-stress Environment

DLP Bioprinting reduces physical stress and pressure on cells during the fabrication process, as it uses light-based polymerization rather than mechanical extrusion⁴. Moreover, DLP bioprinters such as LUMEN X and BIONOVA X, equipped with a temperature regulation system maintain thermal physiological range, combined with visible light (e.g 405 nm) use to minimize photothermal damage and risks of denaturation¹.

Advantages of DLP Bioprinting

Precision, resolution & stiffness CONTROL

High-resolution DLP Bioprinting enables the fabrication of biomimetic tissue models with complex architectures. DLP bioprinters can replicate intricate features found in microvascular networks, fluidic chips, organ-on-a-chip systems, and advanced scaffold designs.

Microvascular networks

DLP Bioprinting enables fabrication of perfusable channels and branching vascular structures down to tens of micrometers, supporting oxygen/nutrient flow and physiological transport like those found in natural vascularized tissues¹˒⁶.

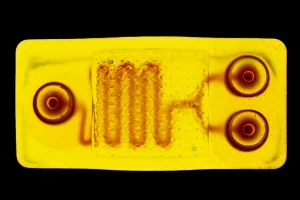

Organ-on-chip models

Custom microfluidic platforms for liver, lung, heart, and tumor-on-a-chip studies use DLP Bioprinting to replicate intricate tissue architecture, accurately simulating human physiology and disease¹˒⁷.

complex scaffolds and surfaces

High-resolution printing supports biomimetic shapes (e.g., gyroid, lattice, microneedles, villi), facilitating tissue-specific functionality, including mechanical support, cell migration control, and surface area expansion, for example, villi for absorption and microneedles for transdermal delivery¹˒⁸.

Stiffness gradient for tissue mimicry

Biological compatibility is the ability of biomaterials and bioprinting processes to support cellular function, viability, and physiological interactions with minimal adverse effects, particularly within tissue-engineered constructs³. With DLP Bioprinting, biological compatibility ensures that bioinks and fabrication methods foster a suitable environment for cells enabling subsequent tissue development and functional maturation.

Reproducibility and fine control

DLP Bioprinting enables reproducibility and fine control over geometry and material placement, essential for physiologically relevant testing such as NAMs and MPS. Multi-material capability and rapid curing further support the scalable production of complex, reproducible biological models, which are essential for reliable experimental comparison and drug testing.

Explore heterogenous models through multi-material DLP Bioprinting

Why multi-material matters

Multi-material DLP Bioprinting allows for spatial control of bioinks, enabling the fabrication of composite structures with distinct biological functions¹¹. By combining multiple photocurable bioinks, each optimized for specific cell types or stiffness levels, DLP bioprinters can reproduce complex tissue architectures.

Guiding cellular function

The ability to control spatial gradients and multi-material configurations directly impacts both cell viability and functional performance of bioprinted tissues¹¹. Gradients in mechanical stiffness or biochemical cues can:

- Guide stem cell fate decisions and support differentiation into target lineages.¹⁴

- Improve integration between engineered and native tissues through optimized mechanical and biological interfaces.¹¹

- Enhance the mechanical resilience of constructs under physiological stress.¹⁵

- Support advanced in vitro models for drug testing, disease modeling, and regenerative therapy research.¹⁶

Real-world applications

DLP Bioprinting is now being utilized by researchers globally, advancing applications such as disease modeling, drug screening, regenerative medicine, microfluidics, and material development, demonstrating the versatility of 3D bioprinting of tissues in real-world biomedical innovation.

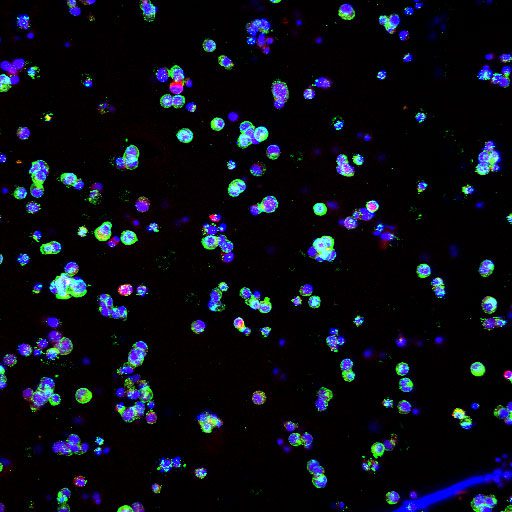

Example case

Perfusable 3D lung cancer models

At Technische Universität Berlin, Professor Jens Kurreck’s team used CELLINK’s DLP bioprinter, the LUMEN X, to fabricate a perfusable 3D lung cancer model with a central vascular channel. The bioprinter’s high-resolution capabilities and effective chemical crosslinking of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) allowed the team to create vascular structures that were both highly precise and exceptionally stable.

Example case 1

Cancer therapy with controlled drug release

Researchers at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore used BIONOVA X to 3D bioprint EV-patches with tunable stiffness for controlled drug release in TNBC (tripple-negative breast cancer) models. By adjusting methacrylation and light intensity during printing, BIONOVA X enabled stiffer scaffolds that prolonged EV release, critical for maintaining anticancer activity and improving therapeutic outcomes.

Example case 2

Intraocular drug implants

A study published in Advanced Science utilized the LUMEN X to fabricate magnetically controllable and degradable milliscale swimmers, designed as intraocular drug implants.

Example case 3

Versatile platform for nasal cell culture

Research published in the International Journal of Pharmaceutics utilized the LUMEN X to create a 3D bioprinted GelMA scaffold, serving as a versatile platform for nasal cell culture and drug testing applications.

Example case 1

3D bioprinted corneal tissue

The Pandorum Technologies team leveraged DLP-based bioprinting with the LUMEN X to prototype and fine-tune the geometric shapes of corneal lenticules, advancing their work toward 3D bioprinted corneal tissue for vision restoration

Example case 2

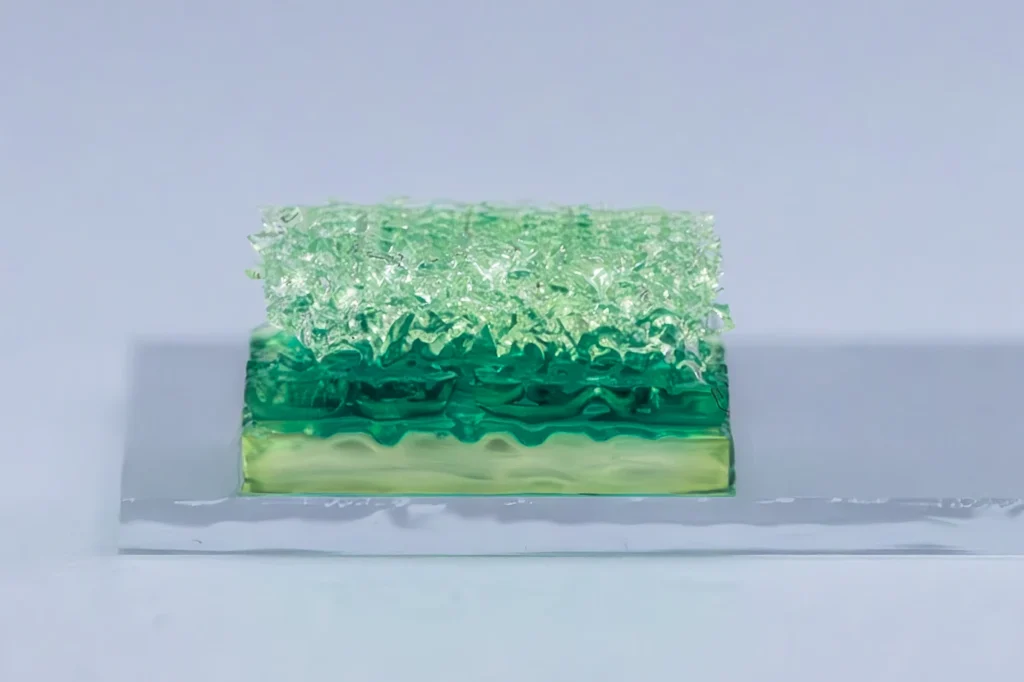

Physiologically relevant meniscal scaffolds

Research published in Advanced Composites Hybrid Materials utilized the LUMEN X for DLP 3D printing of dual crosslinked meniscal scaffolds. The constructs exhibited enhanced physical and biological properties, highlighting DLP’s ability to fabricate anatomically accurate soft-tissue models suitable for musculoskeletal regeneration.

3D printed cornea lenticule using Pandorum Technologies’ proprietary photo-crosslinkable cornea-mimetic bioink and CELLINK’s high-precision light-based bioprinter LUMEN X.

Example case 3

Inducing morphogenesis in specific patterns

Researchers from Irvine University investigating intestinal epithelial morphogenesis used BIONOVA X to fabricate GelMA microwell arrays with tunable geometry and stiffness, enabling precise control over architectural cues in a 2.5D colorectal cancer cell (Caco-2) model. By leveraging BIONOVA X’s high-resolution DLP bioprinting, they decoupled mechanical factors from WNT signaling, revealing that high perimeter-to-area ratios alone could drive epithelial budding and differentiation marker MUC2 expression in Caco-2 cells, shedding light on mechanotransduction’s role in gut tissue formation.¹³

Example case

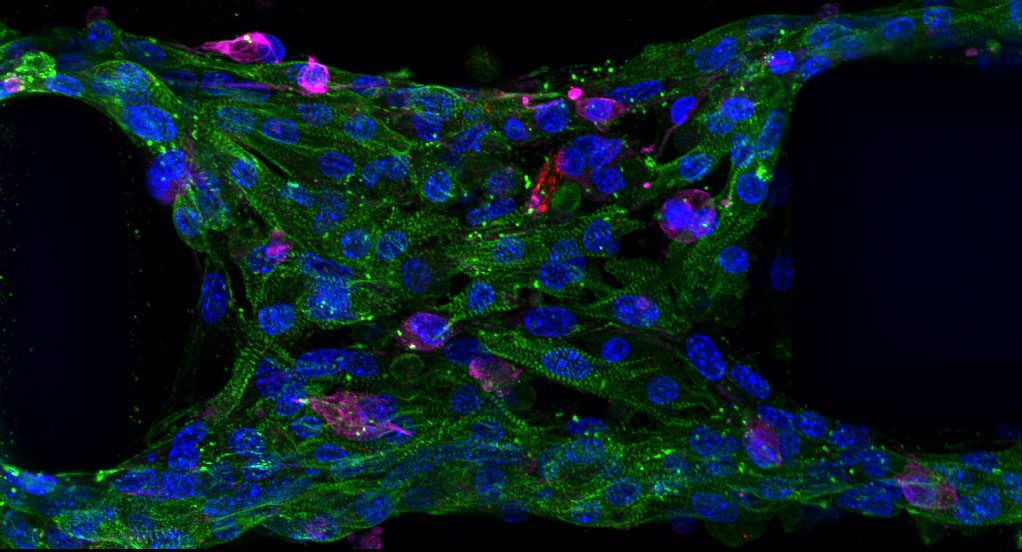

Miniaturized carotid artery model

In a study published in Biofabrication, researchers used CELLINK’s LUMEN X DLP bioprinting platform to create a miniaturized carotid artery model that captured vascular geometry, flow, and endothelial behavior. The construct was printed from GelMA bioink containing human aortic smooth muscle cells, lined with human aortic endothelial cells to form a fully endothelialized lumen. This model demonstrates how light-based bioprinting enables physiologically relevant, patient-specific vascular systems for microfluidic and disease modeling applications.

Example case

Developing and researching new biomaterials

Professor Jeff Bates and his team at the University of Utah develop polymeric formulations that respond to biological or chemical stimuli, enabling analyte sensitivity, triggered release, and controlled drug delivery. The team used a hybrid bioprinting approach, combining extrusion printing through the BIO X™ and DLP-based bioprinting with the LUMEN X. This combination enables the capture of specific geometries that better replicate in vivo environments.

Future outlook

DLP Bioprinting continues to bridge the gap between biological relevance and precision, enabling the scalable replication of cellular environments. With the ability to fabricate high-resolution tissue models, DLP bioprinters advances personalized medicine, where patient-specific constructs can support diagnostics, treatment planning, and regenerative medicine.

The future of DLP Bioprinting lies in hybrid bioprinting modalities that integrate DLP technology and extrusion-based systems, like combining CELLINK’s BIONOVA X or LUMEN X and BIO X. This combination enables researchers to pair fine optical resolution and multi-material versatility, overcoming material and structural limitations.

The synergistic integration of AI and robotics into bioprinting technologies workflows will be instrumental in overcoming current scalability barriers by enabling printing process automation with closed-loop process monitoring and real-time correction. This technological evolution will transform bioprinting into an autonomous data-driven manufacturing standard, which is essential for achieving the standard required by clinical-grade tissue engineering and pharmaceutics drug screening¹². Indeed, as these technologies advance, the translation of DLP-printed constructs into clinical and pharmaceutical applications will also accelerate. Continued collaboration between academia, industry, and regulatory bodies will be key to creating safe, validated pathways for bioprinted tissues to reach the clinic.

At CELLINK, we’re advancing the future of cell-friendly, high-precision bioprinting with our LUMEN X and BIONOVA X DLP bioprinters.

Contact one of our experts to find out how our DLP bioprinters can transform your research, empowering you to design the next generation of tissue models and therapies.

References

- Alparslan C, Bayraktar Ş. Advances in Digital Light Processing (DLP) Bioprinting: A Review of Biomaterials and Its Applications, Innovations, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Polymers. 2025;17(9):1287. doi:10.3390/polym17091287

- Goodarzi Hosseinabadi H, Dogan E, Miri AK, Ionov L. Digital Light Processing Bioprinting Advances for Microtissue Models. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022;8(4):1381-1395. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c01509

- Kim J. Characterization of Biocompatibility of Functional Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting. Bioengineering. 2023;10(4):457. doi:10.3390/bioengineering10040457

- Xu HQ, Liu JC, Zhang ZY, Xu CX. A review on cell damage, viability, and functionality during 3D bioprinting. Mil Med Res. 2022;9(1):70. doi:10.1186/s40779-022-00429-5

- Khan F, Tanaka M. Designing Smart Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;19(1):17. doi:10.3390/ijms19010017

- Lee SY, Phuc HD, Um SH, Mongrain R, Yoon JK, Bhang SH. Photocuring 3D printing technology as an advanced tool for promoting angiogenesis in hypoxia-related diseases. J Tissue Eng. 2024;15:20417314241282476. doi:10.1177/20417314241282476

- Bucciarelli A, Paolelli X, De Vitis E, et al. VAT photopolymerization 3D printing optimization of high aspect ratio structures for additive manufacturing of chips towards biomedical applications. Addit Manuf. 2022;60:103200. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2022.103200

- Wang R, Damanik F, Kuhnt T, et al. Biodegradable Poly(ester) Urethane Acrylate Resins for Digital Light Processing: From Polymer Synthesis to 3D Printed Tissue Engineering Constructs. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12(17):2202648. doi:10.1002/adhm.202202648

- Yi J, Yang S, Yue L, Lei IM. Digital light processing 3D printing of flexible devices: actuators, sensors and energy devices. Microsyst Nanoeng. 2025;11(1):51. doi:10.1038/s41378-025-00885-8

- Wang M, Li W, Mille LS, et al. Digital Light Processing Based Bioprinting with Composable Gradients. Adv Mater. 2022;34(1):2107038. doi:10.1002/adma.202107038

- Ravanbakhsh H, Karamzadeh V, Bao G, Mongeau L, Juncker D, Zhang YS. Emerging Technologies in Multi‐Material Bioprinting. Adv Mater. 2021;33(49):2104730. doi:10.1002/adma.202104730

- Robazzi JVS, Derman ID, Gupta D, et al. The Synergy of Artificial Intelligence and 3D Bioprinting: Unlocking New Frontiers in Precision and Tissue Fabrication. Adv Funct Mater. Published online October 28, 2025:e09530. doi:10.1002/adfm.202509530

- Burmas NC, Fabian AM, Vanavadiya A, Smith Q. Geometrically Controlled WNT Activation Drives Intestinal Morphogenesis. Adv Healthc Mater. 2025;14(23):e2502832. doi:10.1002/adhm.202502832

- Tharakan S, Khondkar S, Ilyas A. Bioprinting of Stem Cells in Multimaterial Scaffolds and Their Applications in Bone Tissue Engineering. Sensors. 2021;21(22):7477. doi:10.3390/s21227477

- Menon A, Elkhoury K, Zahraa A, et al. Digital light processing 3D printing of dual crosslinked meniscal scaffolds with enhanced physical and biological properties. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2025;8(1):92. doi:10.1007/s42114-024-01196-8

- Wong CYJ, Ong HX, Traini D. Three-dimensional bioprinted gelatin methacryloyl scaffold: a versatile platform for nasal cell culture and drug testing applications. Int J Pharm. 2025;681:125803. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2025.125803