Understanding Bioelectronics

How Bioprinting is Used to Print Soft, Conductive Materials

As the lines between biology and technology continue to blur, one field is seeing an ever-increasing interest from researchers — bioelectronics.

Bioelectronics refers to the integration of electronic systems with biological systems. It is the science of creating devices that can monitor or interact with the body’s natural processes. An example of bioelectronics seen in everyday life is the fitness tracker. Wearable fitness trackers can, for example, track heart rate, blood oxygen levels, and sleep patterns.

While fitness trackers are one of the most common examples of bioelectronics, wearable health monitors (such as real-time glucose meters) and implantable devices (such as pacemakers) are other common forms of bioelectronics in use today.

Bioprinting and Bioelectronics

The list of applications in bioelectronics can be greatly expanded using flexible and biocompatible materials. This is where 3D bioprinting comes in.

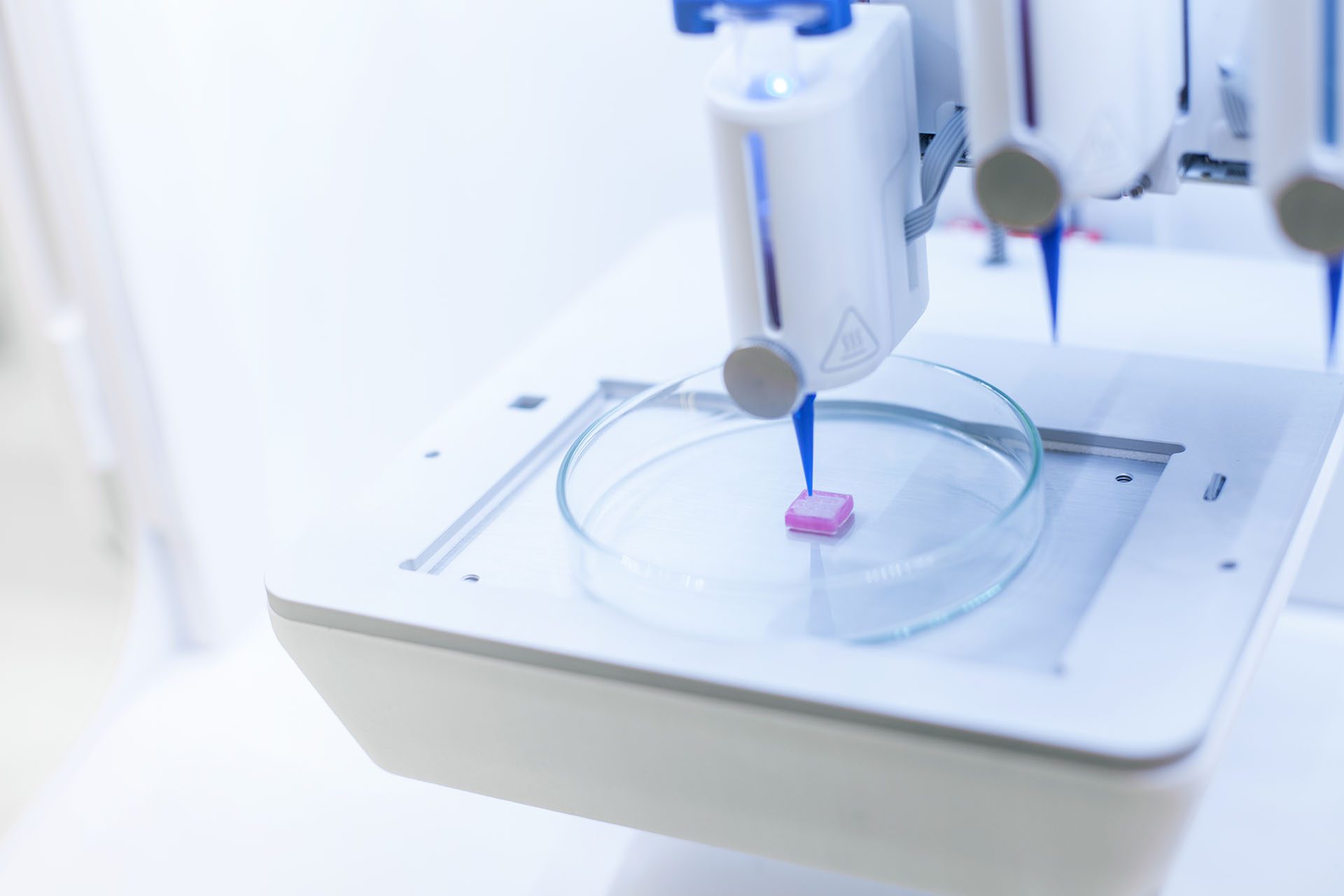

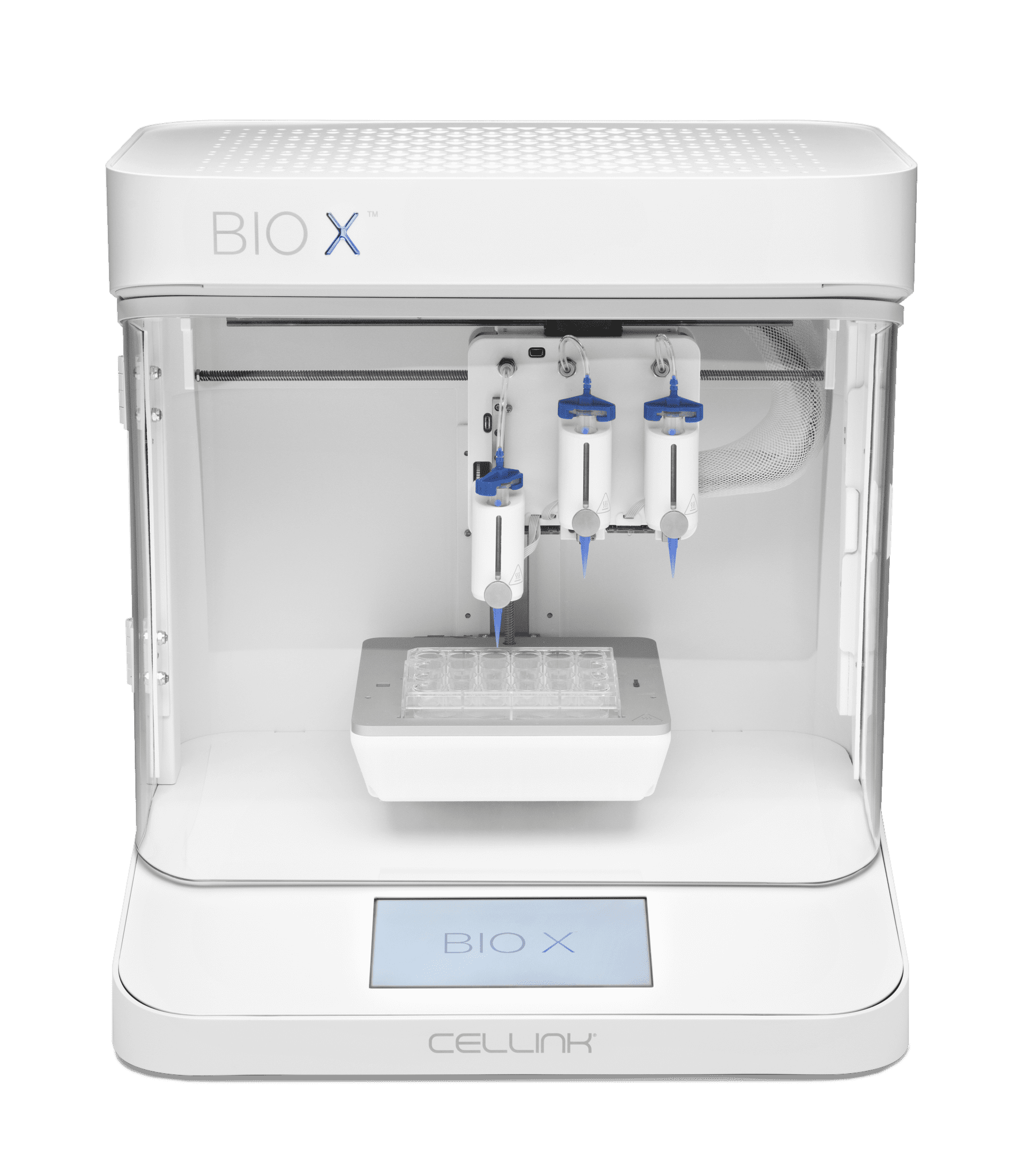

Multi-material bioprinting is a valuable tool for bioelectronics as it allows for the integration of biological materials with electronically conductive components. A multi-material bioprinter allows for the precise placement of tissue-forming and functional materials, giving unparalleled control over the design and composition of the tissue.

By using biocompatible materials and printing with cells, bioprinting allows for the personalization of implantable bioelectronic devices, reducing the risk of immune rejection.

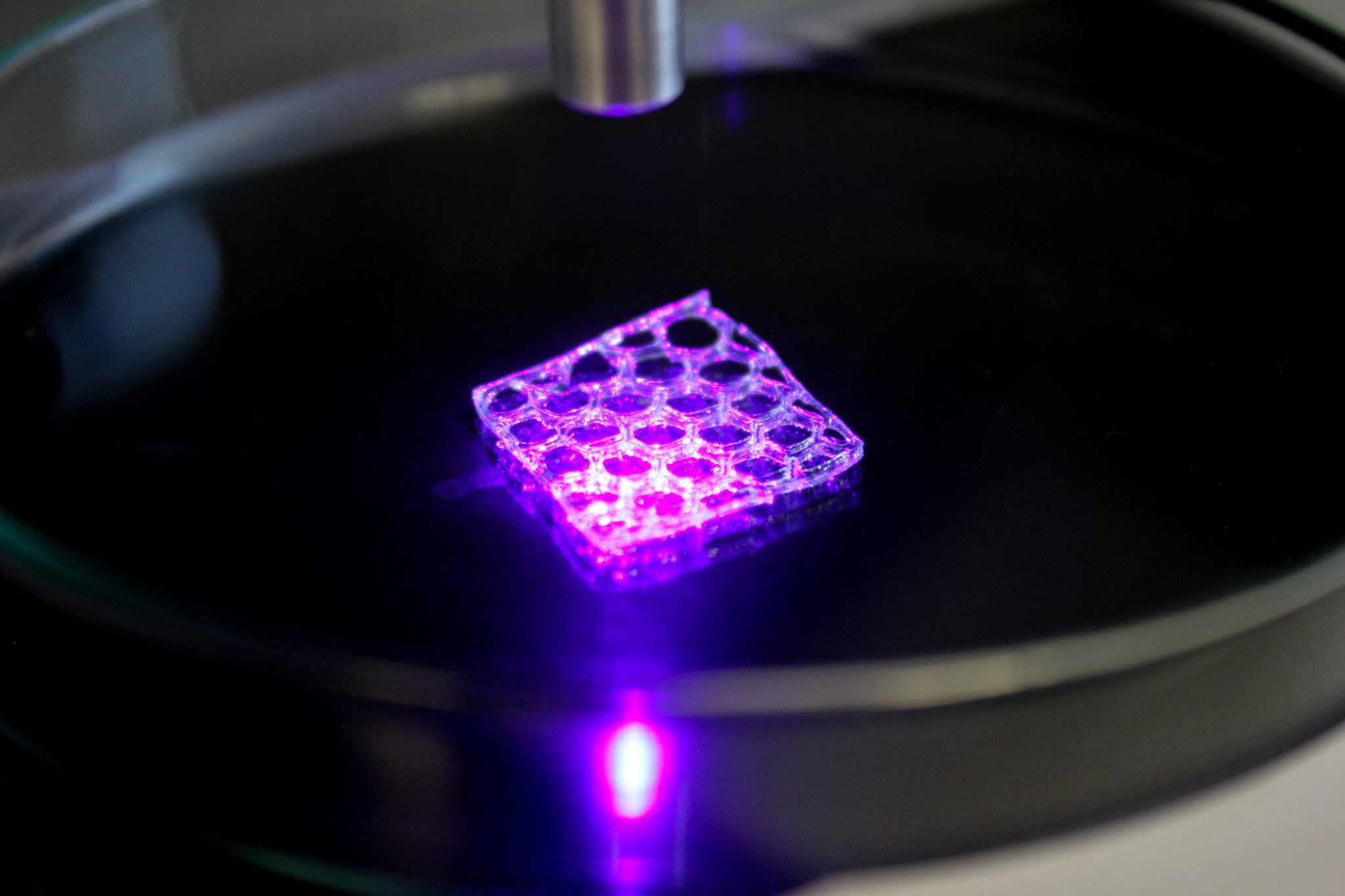

In addition to the ability to customize the tissue to your needs, bioprinters are designed to print with soft materials, which allow for the printing of flexible constructs. This means that 3D bioprinting is also an excellent tool for the 3D printing of acellular, but biocompatible, soft electronics constructs.

How Researchers Combine 3D Bioprinting and Bioelectronics

To better understand how researchers are using CELLINK’s bioprinters to enhance and improve bioelectronic applications, we have spoken to Dr. Miriam Filippi.

Dr. Miriam Filippi is Senior Scientist of Bio-hybrid Robotics at the Soft Robotics Lab (SRL, led by Prof. Robert Katzschmann) at ETH Zurich (ETHZ). Her team recently published a study on the topic in Advanced Healthcare Materials, in a collaborative effort with EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Dr. Filippi emphasizes the multi-disciplinary skills required to succeed in the bioelectronics space, saying, “Our team’s expertise comes together like a puzzle to cover all the relevant aspects needed to succeed in our bioengineering realization.”

She continues, “The team works with an unwavering commitment and tireless effort to propose a new vision of tissue engineering and robotics. We are driven by genuine enthusiasm for bioelectronic innovation, and we let our creativity fly in the pursuit of advanced tissue models.”

The Team

Involved in the Soft Hydrogel team at SRL in ETHZ are:

Dr. Miriam Filippi – an established researcher and the principal investigator of bio-hybrid robotics in the SRL with expertise in biomanufacturing, functional materials, and tissue development.

Dr. Antonia Georgopoulou – a postdoc at the Soft Materials Laboratory at the EPFL (Lausanne, Switzerland) with expertise in sensors, robotics, and material science.

Asia Badolato – a Ph.D. student at the SRL with expertise in tissue biomechanics and 3D bioprinting.

Diana Mock – a Master student at the SRL with expertise in multi-material 3D bioprinting and tissue engineering.

From left to right: Diana Mock, Asia Badolato, Dr. Miriam Filippi, and Dr. Antonia Georgopoulou.

The Research

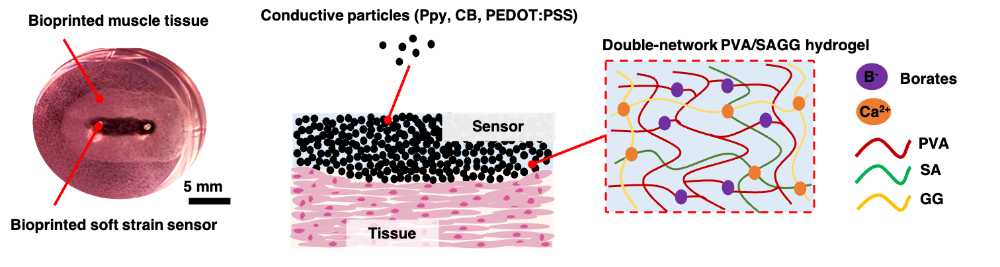

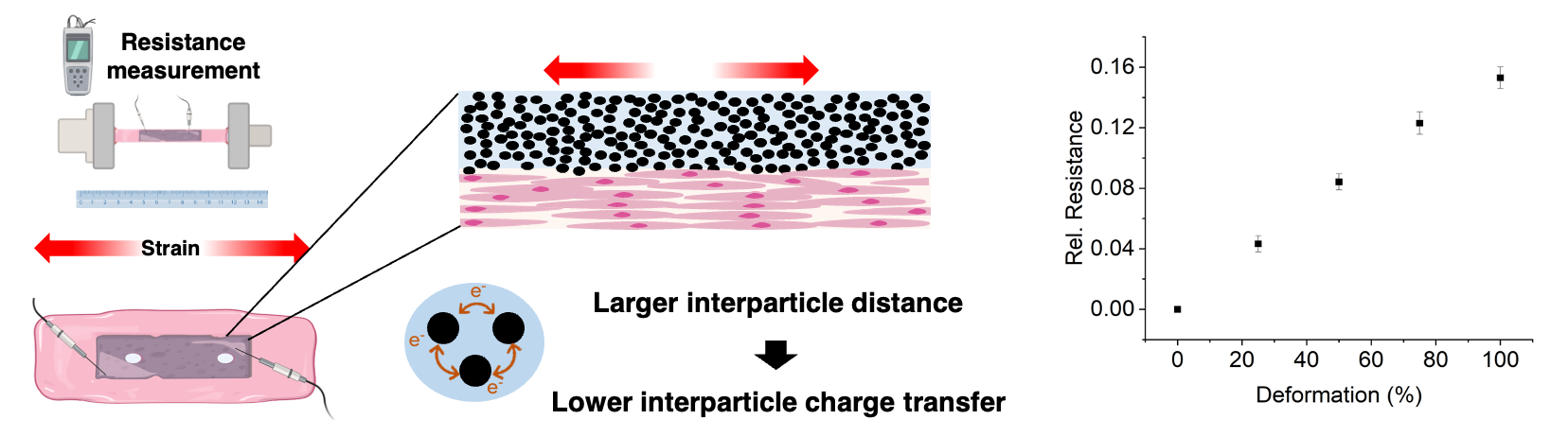

In the study, titled Bioprinting of Stable Bionic Interfaces Using Piezoresistive Hydrogel Organoelectronics, the team sought to create a material with high tissue integration capabilities, and importantly, a mechanism to capture responses to biomechanical cues.

This was achieved through a “sensor hydrogel” which could be integrated within their bioprinted construct.

The researched developed this sensor hydrogel by combining the synthetic hydrogel PVA with the natural hydrogels Sodium Alginate (SA) and Gellan Gum (GG), and a conductive filler. In the study, they tested two different conductive fillers: Polymer Polypyrrole (PPy) and Carbon Black (CB).

Both composites had similar sensor characteristics when characterized, however, the CB-composite had the undesired tendency to agglomerate, which the PPy-composite did not. That is why the research team selected the PPy-composite as a material with the potential for 3D fabricating a tissue-embedded sensor.

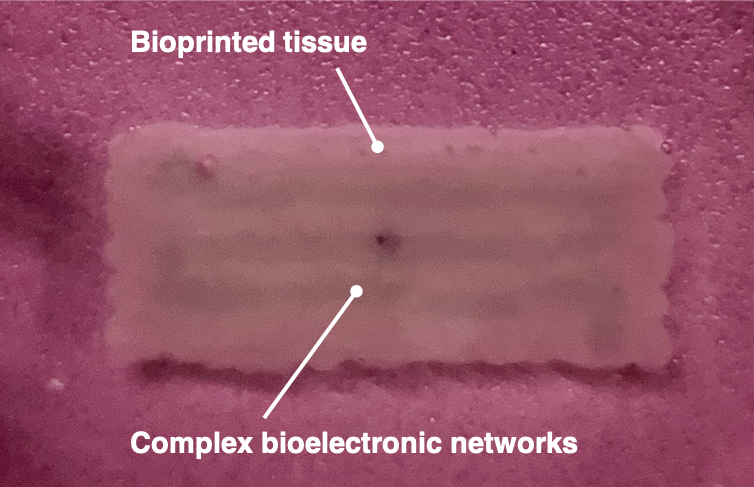

The sensor hydrogel was printed alongside a cell-seeded muscle-tissue bioink, using CELLINK’s BIO X6 3D bioprinter. The printed muscle tissue with the integrated sensor was then cultured to mature the tissue. Following the culture process, the team tested the tissue model’s sensor performance.

The Challenge of Complex Material Combinations

We asked Dr. Miriam Filippi to tell us more about the challenges of working with multiple materials that have distinct characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages. In addition to the complex composition of the sensor hydrogel, the researchers needed a bioink which could support tissue growth. The bioink they developed is a composite of the naturally derived materials Matrigel and collagen.

“In our work routine, the main challenge was to combine the different operative requirements for handling these complex combinations of materials. For example, Matrigel and collagen have crosslinking behavior that is temperature-sensitive but with sensitivity to different temperature ranges. Chemical crosslinking was needed to stabilize other components. In addition to crosslinking, printability had to be optimized through intense work.”

Dr. Filippi goes on to describe that the mixture’s complexity made it a challenge to ensure the bioink would react the same across batches and time, until they figured out the correct protocols.

Why Complex Materials Were Needed

The reason the SRL team opted for complex ink formulations was the need to control multiple parameters: stability and viscosity, double-hydrogel network formation, the combination with conductive components, and tissue-specific requirements.

While the sensor hydrogel was optimized for high-resolution printability and piezoresistive behavior, the tissue-bioink was optimized to develop skeletal muscle tissue. Together, the formulations were conceived to interconnect in the bioprinted structure.

Next Steps

Dr. Filippi is confident that the printed tissue constructs have the potential to provide information on what is happening inside a tissue, for example to measure strain.

She says, “While our sensor material can reliably respond to certain types of mechanical stimuli, like gross bulk structural deformation of the tissue, the fine-tuning of the sensor’s functionality and its ability to detect deformations of smaller entities are yet to be assessed,” and continues:

Dr. Miriam Filippi

“For example, our functional hydrogels could serve to assemble conductive pathways within the engineered tissue, creating anisotropic electric conductivity. As a result, tissues with electrochemical functionalities, such as neural and muscle tissue, could be designed and realized according to specific, tailored patterns, leading to innovative 3D cell culture models with complex, controllable growth and functionality.”

How to approach the printing of tissue-integrated bioelectronics

We spoke to Dr. Filippi to get a better idea of how they approached their objective: to print biphasic constructs containing both sensing hydrogel and myoblast-laden matrix.

The team took 10 clear steps to go from the print to final construct. These can be categorized in three phases: Pre-bioprinting, Bioprinting, and Post-bioprinting.

Pre-Bioprinting

In this phase, the research team prepared the 3D models and materials needed to create the constructs.

- A tailored G-Code was written to tell the BIO X6 to build the construct with a certain architecture and distribution of the two materials.

- First, they prepare the sensor hydrogel by weighing all ingredients and mixing them under specific, controlled conditions (e.g., stirring, controlling the temperature).

- Crosslinking solutions are prepared at the same time.

- To create the cell-laden bioink, the cells were counted, a specific number of cells were centrifuged, collected as pellets, and then mixed into the bioink at a pre-determined number with a certain volume of bioink. This ensures a consistent cell-to-bioink ratio.

Bioprinting

In this phase, the materials are loaded in their respective cartridges, parameters are set (and saved), and the printing commenced.

- The cell-laden bioink and the sensor hydrogel were aseptically loaded into different cartridges and extruded through conical 22G nozzles.

- Before printing, the nozzles were calibrated to determine their respective XYZ offsets with a minimum of 01 mm accuracy.

- The team set up the BIO X6 to work with an optimized set of printing parameters (incl. pressure, speed, and temperature) determined in prior optimization experiments by assessing the strand printing accuracy and shape fidelity. The printing procedure was optimized to maximize the cell seeding density while retaining good mechanical properties of the resulting bioink that allowed for accurate printing.

- The 3D bioprinting process was started and the construct obtained.

Post-Bioprinting

In this phase, the researchers cultured the constructs according to the needs of the cells (myoblasts). They then proceeded with testing the resulting tissue samples.

- The constructs were moved to tissue culture plates and placed in an incubator. The cell-laden constructs were supplemented with a growth medium for 4 days to allow for cell proliferation. Half of the volume of the culture media was collected and replaced each day. As the research team used myoblasts to create muscle tissue, the constructs were matured under mechanical tension.

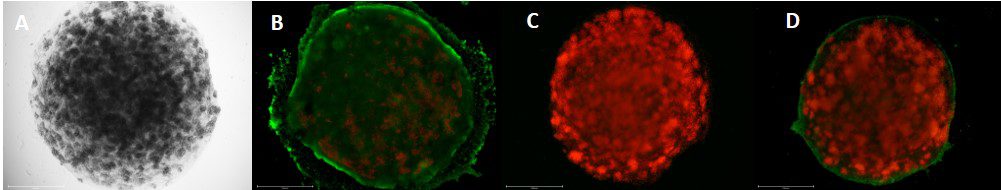

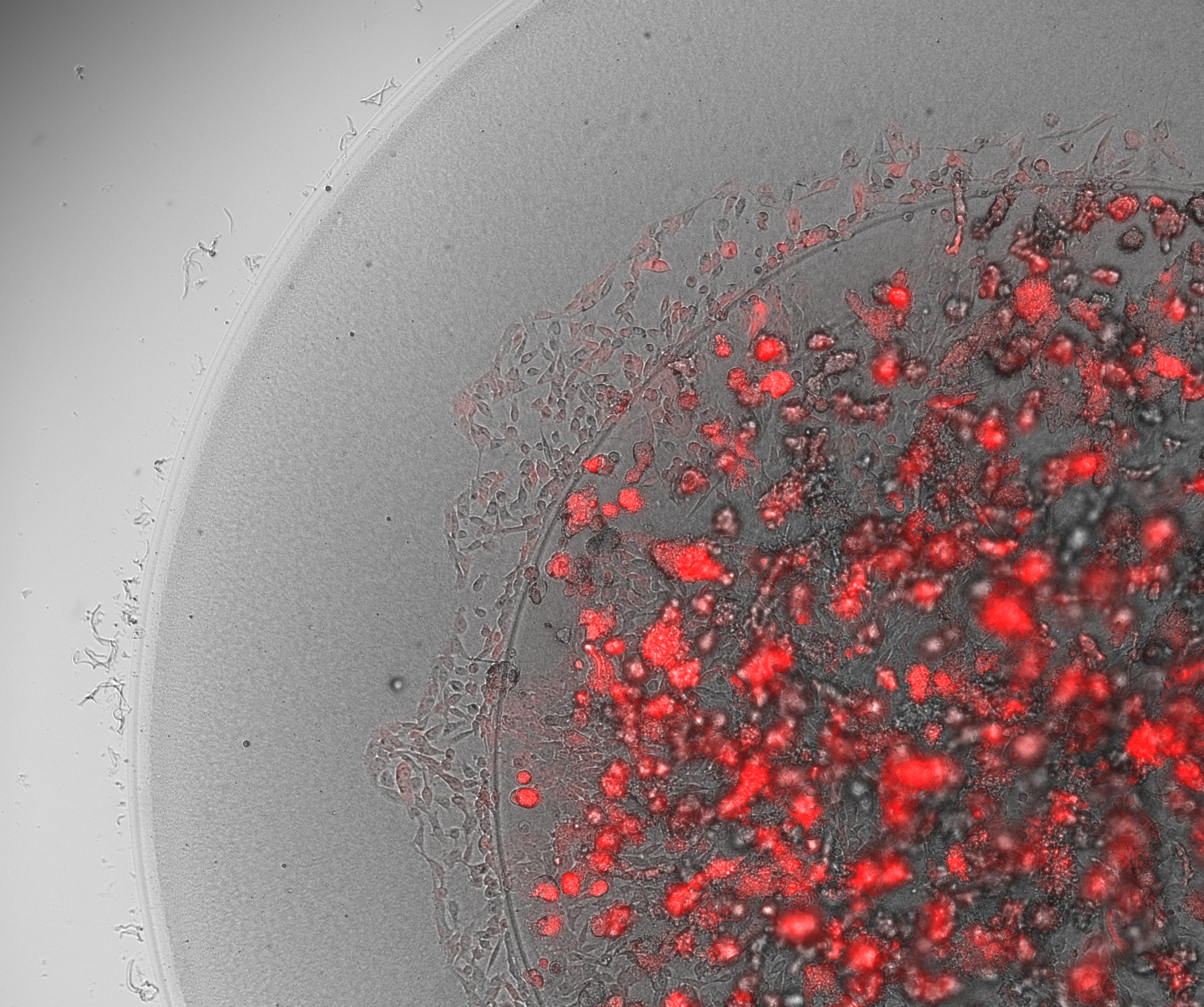

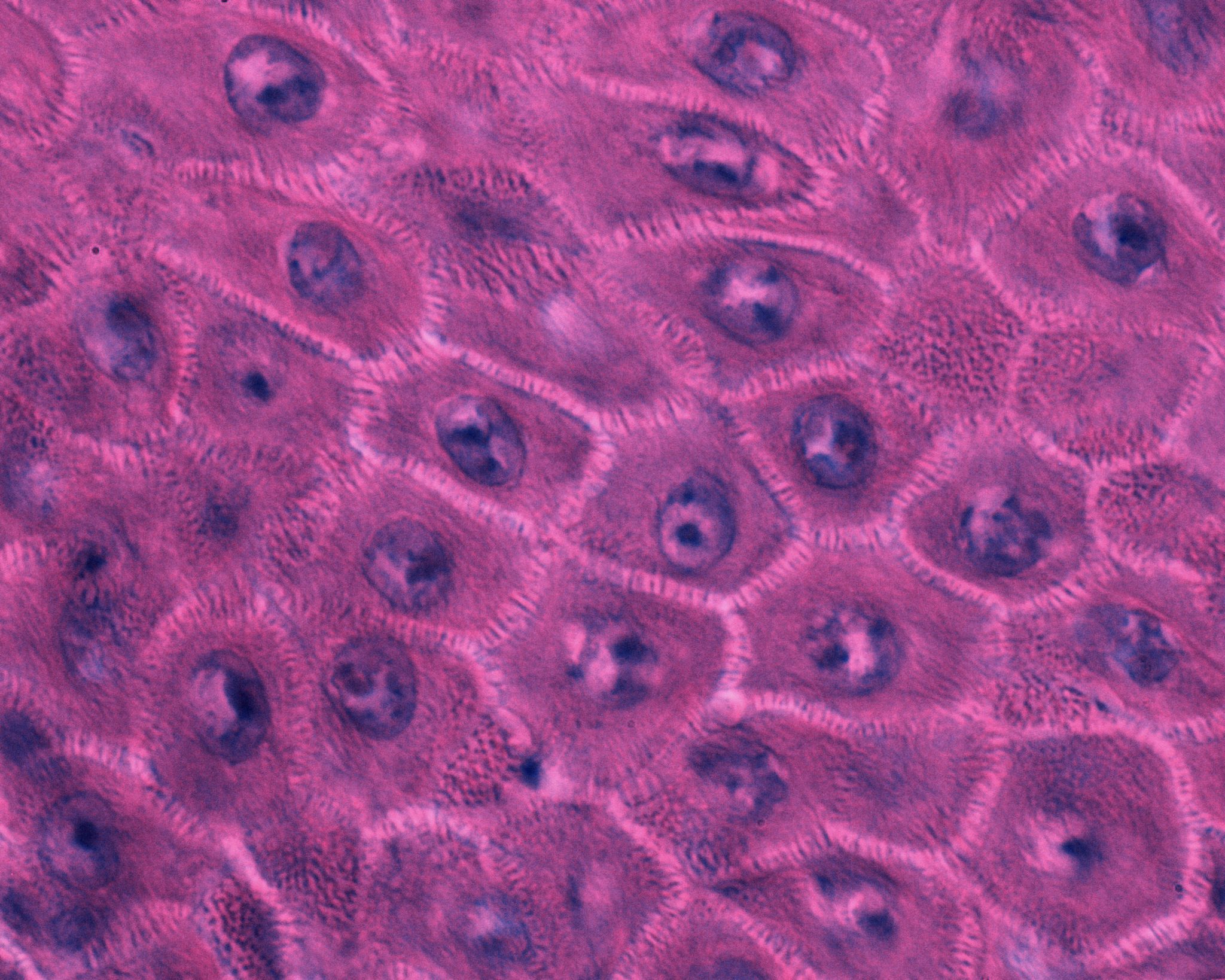

- After the tissue maturation was completed, the engineered tissue samples were distributed to different experimental flows to run the needed analysis. This included Live/Dead Staining to test viability under confocal imaging, histological tissue sectioning for cell expression staining, and mechanoelectrical and rheological characterization of the tissue.

Conclusion

In this blog, we have looked at how 3D bioprinting and bioelectronics can interplay. We have delved deeper into a specific case from Dr. Filippi’s team at the Soft Robotics Laboratory at ETH Zurich, where a conductive sensor hydrogel is directly integrated with 3D printed tissue.

Other applications of 3D printed soft electronics don’t focus on specific tissue. Instead, these applications utilize the 3D bioprinter’s unique capability to precisely shape biocompatible, conductive constructs. These constructs can then be used in many ways. An example of this can be found in this publication, by Steve Park’s lab at KAIST.

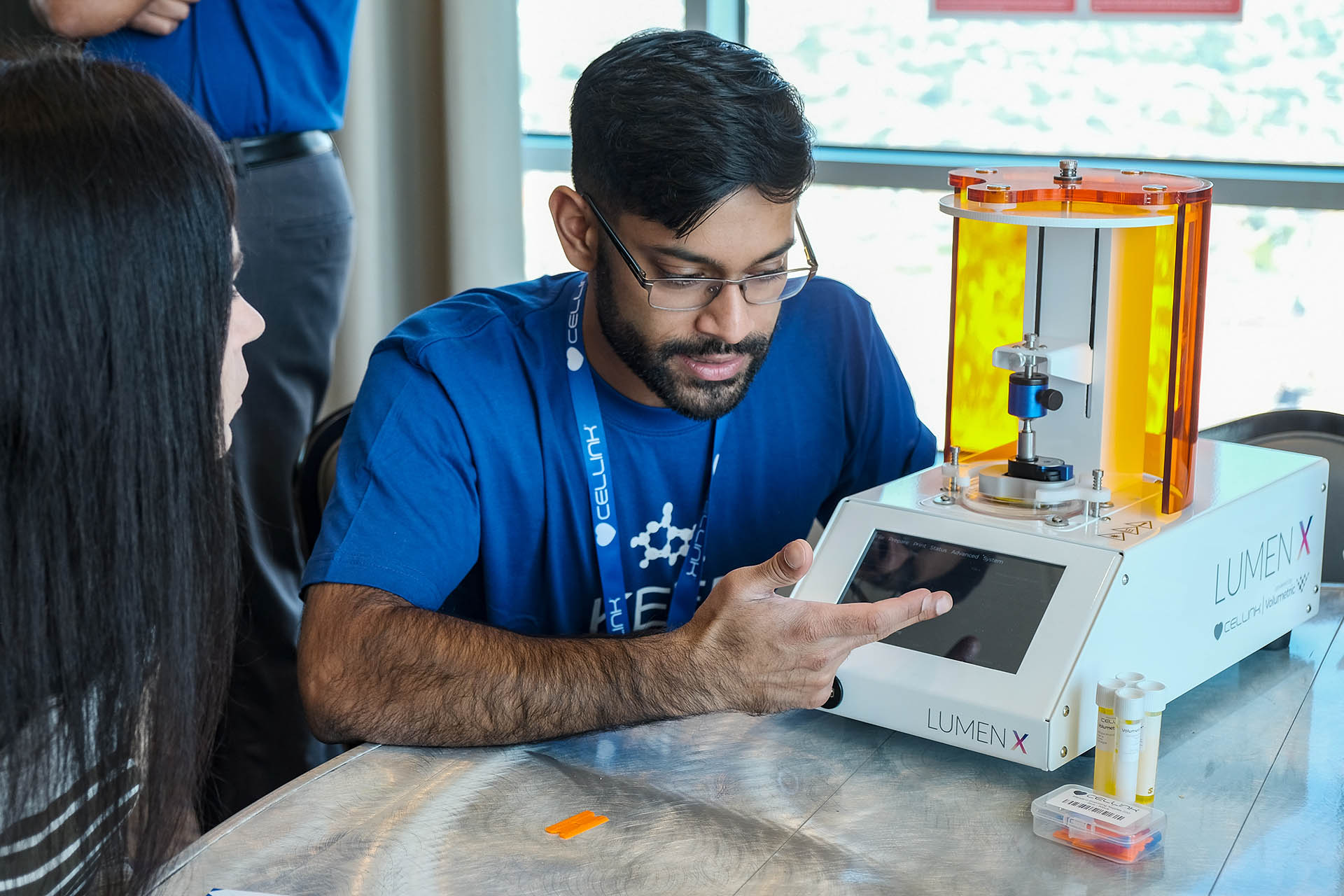

Multi-material bioprinters, like the BIO X6, give the researchers full control to construct the architecture however they want, with either ready-made or custom materials. CELLINK has focused on making it as easy and as possible for researchers with different backgrounds to take advantage of everything bioprinting has to offer.

Are you interested in printing soft electronics or biosensors, or are you otherwise in need of a 3D bioprinter?

Don’t hesitate to contact us here, and we would be happy to show you more.

Read More

Publication: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/adhm.202400051

Soft Robotics Lab: https://srl.ethz.ch/

BIO X6 – 3D Bioprinter: https://www.cellink.com/bioprinting/bio-x6-3d-bioprinter/